The Complex Legacy of John Ireland

MONUMENTS TO THE FAITH

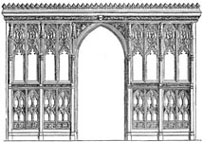

Twice a year, Catholics in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis gather on the grounds of the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul and process down John Ireland Boulevard, reciting Rosaries on the way to the magnificent cathedral. John Ireland, archbishop from 1888 to 1918, is most noteworthy, at least to historians, for his identification — fairly or not — with the heresy of Americanism. Indeed, this subject is a persistent theme in Fr. Marvin O’Connell’s fine biography, John Ireland and the American Catholic Church (1988). But as a native Minnesotan and a parishioner of the Cathedral of St. Paul, I primarily associate Archbishop Ireland — yes, he was indeed Irish — with French transplant Emmanuel Masqueray, the brilliant architect who helped build our cathedral, as well as the Basilica of St. Mary in Minneapolis.

The age of the automobile has artificially shortened distances, and it now takes about 15 minutes to drive the ten miles along I-94 between the two churches — perhaps longer if traffic is heavy around uptown. Suffice it to say that a century ago, travel was much more difficult — and time-consuming. So, Masqueray was kept busy, bustling back and forth between the two projects Ireland had undertaken, “with characteristic bravura,” as O’Connell puts it, simultaneously.

I do not claim to be impartial when it comes to assessing the beauty of the cathedral in which I married my wife and in which all four of our children were baptized. I find myself in agreement with our new pastor, who asserted in a recent homily that it is the most majestic building on the continent. Probably the first thing that strikes visitors is the size of the edifice — my kids call it “the big church,” to which all others shall be compared and dubbed “little.” The cathedral is just over 300 feet tall, but because it stands on Summit Hill, it looms larger.

You May Also Enjoy

We Catholics have nowhere near the influence that our numbers and organization would suggest. Man for man, woman for woman, the U.S. Catholic community has a surprisingly modest impact on American public life.

Catholicism is a 'general culture' that inculcates a way of life and encompasses a whole realm of unspoken and spontaneous things in daily life.

The conservative disposition, forever disinclined to learn from the Left's successful strategies, is handicapped in the culture war.