“The Pardoner’s Tale.” By Geoffrey Chaucer.

LITERATURE MATTERS

Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is one of the great works of English literature. Not only does this encyclopedic compendium of every known medieval genre capture a wide range of universal themes regarding human goodness and weakness, it is thoroughgoing entertainment. Chaucer is, first and foremost, a satirist of human foibles and professional quirks. He throws together a group of 30 pilgrims from every walk of life who have gathered at London’s famous Tabard Inn, just south of the Thames, to make a spring pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury’s cathedral. The Tabard’s publican, a stout fellow by the name of Harry Bailey, proposes a storytelling competition to help pass the time along the pilgrims’ way. One of the most enduring of these stories is “The Pardoner’s Tale.”

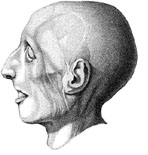

In this tale and its prologue, Chaucer condemns the pardoner’s vice by wit and the sheer outrageousness of the character’s portrayal. It is no coincidence that the pardoner is described as ugly and effeminate with a host of metaphors that equate him with the lesser traits of the animal world. His physiognomy reveals the sorry state of his soul: His hair falls in rat-tails, his eyes bulge like a hare’s, and his voice sounds like a goat’s. Overall, the pardoner is compared to a gelding, a castrated male horse. None of these physical quirks, however, keeps him from cultivating a condescending attitude and a haughty kind of speech. When it comes time for him to spin his yarn, he boasts not only of his skill at preaching — and he is most definitely an accomplished sermonizer — but also of his moral and religious hypocrisy. This is where Chaucer is arguably at his best: criticizing not devotion and religion itself but lampooning the perversions and distortions of the faith, especially by those men of the Church — and those who claim to act in her name — who use religion for their own personal financial gain.

A so-called pardoner in those days was an emissary of Rome, charged with delivering official documents to local churches, including papal bulls, indulgences, and pardons. For those listening closely to the pardoner’s preamble to his own story, he not only reveals that he’s a fraud, he brags about it:

I speak some words of Latin — just a few —

To put a saffron tinge upon my preaching

And stir devotion with a spice of teaching.

Then I bring all my long glass bottles out

Cram full of bones and ragged bits of clout.

Relics they are, at least for such are known.

Then cased in metal, I’ve a shoulder bone,

Belong to a sheep, a holy Jew’s.

You May Also Enjoy

Lust is not beautiful, and no rhetoric can make it seem so. In "Sonnet 116," Shakespeare reminds us of what love really is: "the marriage of true minds."

Willa Cather understands there’s a bleak side to the Romantic ideal of the American dream, a critical misinterpretation that the dream focuses on you rather than on others.

Today sensitivity is a virtue, stimuli are irresistible, environment is determinative, and we prefer our chicken frozen and wrapped in plastic.